Digital Cinema Package

- sharmistha

- Mar 22, 2025

- 10 min read

Before DCPs took over, films were shipped around the world as 35mm and 70mm prints—heavy, expensive, fragile. By the late '90s, Hollywood was desperate for something cheaper, more secure, and actually built for the digital age. Enter the first major digital screenings in 1999, with Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace leading the charge. But with no universal standard, the whole thing was a mess—different formats, different encryption methods, and plenty of compatibility nightmares.

By 2002, the major studios had had enough. They formed Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) to clean up the chaos and, in 2005, dropped DCI 1.0—a set of strict rules that turned digital projection into a real, functioning system. JPEG 2000 compression, MXF-wrapped files, XYZ color space, encryption, KDMs—everything finally had a standard. But before the industry fully switched over, an early, more basic version called Interop DCP ruled the scene from 2005 to 2012. It worked, but it was limited—no encryption, no high frame rates, clunky subtitle support. It was a patchwork solution while the real system was still being built.

By 2009, SMPTE-compliant DCPs started rolling out, but it took a few years before theaters fully adopted them. By 2012, the transition was mostly complete, with SMPTE DCPs officially replacing Interop as the global standard. Now, encryption was in place, high frame rates (25, 30, 48, 60fps) were supported, and subtitles finally worked properly. From there, DCP tech kept evolving—The Hobbit and Avatar: The Way of Water pushed high frame rates into mainstream films, HDR formats like Dolby Vision started creeping in, and 4K became the default. Even 8K is being toyed with. Meanwhile, the way DCPs get delivered is changing too—hard drives (CRU drives) have been the go-to for years, but cloud-based distribution is picking up speed, making digital film delivery faster and smoother than ever.

A DCP (Digital Cinema Package) is the industry-standard format for delivering digital movies to theaters. It consists of a set of files that contain the video, audio, subtitles, and metadata needed for a cinema projector to play the film.

Key Features of a DCP:

Video: Typically in JPEG 2000 format, encoded in XYZ color space for accurate color reproduction, wrapped in an MXF file.

Audio: Uncompressed 24-bit Linear PCM file, often in 5.1 or 7.1 surround sound (multichannel WAV), wrapped in an MXF file.

Subtitles: In DCP XML format, allowing for multiple language options.

Metadata: Includes information such as the frame rate, aspect ratio, and encryption details (if applicable).

Why is a DCP Used?

Ensures high-quality, standardized playback across all digital cinema projectors.

Supports DRM encryption (KDM - Key Delivery Message) to prevent piracy.

Compatible with DCI (Digital Cinema Initiatives) specifications, making it the global standard for theaters.

Common DCP Specs:

Resolution: 2K (2048×1080) or 4K (4096×2160)

Frame Rate: 24fps, 25fps, 30fps, or HFR (48/60fps)

Bit Depth: 12-bit per channel

Compression: JPEG 2000

DCPs are created using specialized software like EasyDCP, DCP-o-matic, or Clipster and tested in cinema servers to ensure proper playback.

DCDM stands for Digital Cinema Distribution Master.

DCDM is the intermediate master format used before creating a DCP (Digital Cinema Package). It is a high-quality, uncompressed, and color-accurate master file used as the final reference for creating a Digital Cinema Package (DCP). The DCDM is typically in XYZ color space and consists of separate image, audio, and subtitle files. It ensures that the film retains its highest quality before compression and encryption for theatrical distribution.

What You Need to Create a DCP (Digital Cinema Package) :

To create a Digital Cinema Package (DCP), you’ll need to provide the following elements:

1. Video (Picture Track)

Format:

TIFF image sequence (16-bit DPX or PNG can work, but TIFF is preferred)

ProRes 4444 (sometimes accepted for conversion)

Resolution:

2K DCP → 2048×1080

4K DCP → 4096×2160

Frame Rate:

24 fps (Preferred Standard)

25 fps, 30 fps, 48 fps, 60 fps (less common, requires special setup)

Color Space:

DCI-P3 (Preferred for theatrical projection)

Rec.709 (if grading was done for broadcast, but will need conversion)

Bit Depth:

12-bit XYZ (DCP conversion step)

2. Audio (Sound Track)

Format:

24-bit Linear PCM WAV

48kHz or 96kHz (48kHz preferred for standard DCPs)

Multichannel (5.1 or 7.1) or Stereo (L, R)

Channel Mapping:

Stereo: Left (L), Right (R)

5.1 Surround: L, R, C, LFE, LS, RS

7.1 Surround: L, R, C, LFE, LS, RS, LRS, RRS

3. Subtitles (If needed)

Format:

DCI XML (can be converted from srt)

Placement: Preferably a separate XML subtitle track

Final Step: DCP Encoding & Packaging

Once you have these assets, they will be converted to JPEG 2000, encoded to XYZ color space, and wrapped into an MXF container.

A CPL (Composition Playlist) and PKL (Packing List) will be generated to organize the DCP.

If encryption is needed, a KDM (Key Delivery Message) will be required for playback on a cinema server.

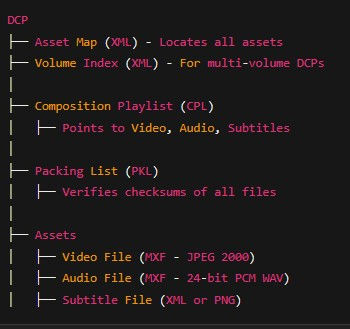

The DCI (Digital Cinema Initiatives) Object Model defines the hierarchical structure of a Digital Cinema Package (DCP). It represents how different elements interact within a DCP, ensuring proper playback in digital cinema systems.

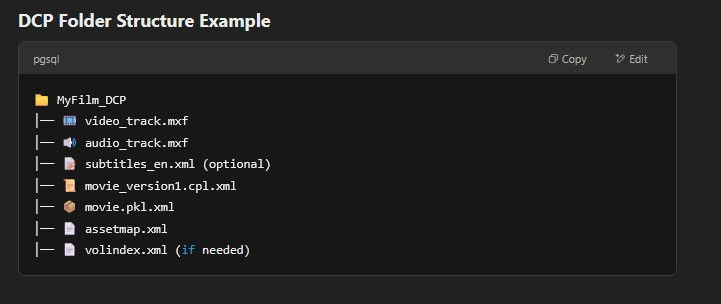

Understanding DCP File Structure: Assetmap, CPL, PKL, VOLINDEX

A Digital Cinema Package (DCP) is made up of multiple files. The obvious parts are : the video (picture track), audio and subtitles, but there are some specialized files like CPL, PKL, Volindex and Assetmap. Without these files, the cinema server won’t know how to read, play, or verify your DCP. If any of these are missing, the DCP might not ingest or play correctly.

1. Assetmap

📌 What it does:

The "table of contents" for the DCP.

Lists all the files (video, audio, subtitles, metadata) inside the DCP and their locations.

DCP contains multiple MXF files for video and audio, plus metadata files. The Assetmap tells the cinema server where each of these files is stored.

2. CPL (Composition Playlist)

📌 What it does:

The "blueprint" or "edit decision list" for the film.

Defines the playback order (of reels), timing, and metadata for each track (video, audio, subtitles).

The picture and sound is identified with UUID (Universally Unique Identifier)

A DCP can have multiple CPLs (for different versions, e.g., different languages or aspect ratios).

your film has multiple audio languages, each CPL tells the system which video + which audio to play.

3. PKL (Packing List)

📌 What it does:

A "manifest" or "inventory list" that ensures all DCP files are intact.

Includes checksums (a digital fingerprint) to verify that no files are corrupted or missing.

It has a 'hash value' that can verify if the same file has been copied or not. By matching hash value, one can identify from where the file has been pirated.

During ingestioninto the server, the hash values are verefied to confirm that the data is not corrupt or tempered with.

Before ingesting a DCP, the cinema’s server checks the PKL to confirm all files are present and unaltered.

4. VOLINDEX (Volume Index)

📌 What it does:

Used when a DCP is too large for a single storage device (e.g., multiple hard drives).

Helps the cinema system understand how many parts there are and how to assemble them.

Mostly a placeholder now. No longer used.

A film distributed across two hard drives will have a VOLINDEX file on each, helping the system recognize it’s one film split across multiple volumes.

CPL is like a movie script (it dictates what plays and when).

PKL is like a checklist (it ensures all files are there).

Asset Map is like an index (it tells the system where things are stored

DCP Supported Frame Sizes & Aspect Ratios

DCPs support three primary aspect ratios: Full, Flat, and Scope. Here’s how they break down in both 2K and 4K resolutions:

Format | Aspect Ratio | 2K Resolution | 4K Resolution |

Full (DCI) | 1.90:1 | 2048 × 1080 | 4096 × 2160 |

Flat | 1.85:1 | 1998 × 1080 | 3996 × 2160 |

Scope | 2.39:1 | 2048 × 858 | 4096 × 1716 |

Do Most Theaters Have Scope?

Yes, most traditional cinemas are designed for Scope (2.39:1) projection. The reason? Cinemascope has been the dominant widescreen format since the 1950s, giving that "cinematic" look. Theaters usually have screens optimized for Scope, and anything outside that ratio requires masking or adjustments.

How Do You Project 16:9 (Flat) on Scope Screens?

If a theater screen is Scope (2.39:1), but the film is Flat (1.85:1 or 16:9), there are two ways to project it:

With Side Pillarboxing (Black Bars on the Sides) – The image is centered within the Scope screen, leaving unused black areas on both sides. This maintains the correct aspect ratio.

Zoomed In (Cropping the Top & Bottom) – Some theaters may zoom in to fill the width of the Scope screen, but this cuts off the top and bottom of the frame. Not ideal, but it happens.

Flat vs. 16:9 – What's the Difference?

Flat (1.85:1) = 1998×1080 (2K) or 3996×2160 (4K)

16:9 (1.78:1) = 1920×1080 (HD) or 3840×2160 (UHD/4K TV)

1.85:1 (Flat) is slightly wider than 16:9, meaning if you project a 16:9 video on a Flat screen without adjustments, you’ll get thin letterbox bars at the top and bottom.

How is 16:9 Handled in DCPs?

Since DCPs don’t officially support 16:9 as a native format, you usually:

Fit 16:9 inside Flat (1.85:1) – This adds small black bars on the left and right.

Fit 16:9 inside Full (1.90:1) – This is closer but still has slight cropping or bars.

Crop to 1.85:1 (Flat) – The top and bottom are slightly trimmed to fit exactly.

For cinemas, Flat (1.85:1) is the closest match to 16:9. Most theaters don’t project in Full. They use either Flat (1.85:1) or Scope (2.39:1), adjusting the masking and lens to fit one of those formats.

Markers in DCP

Markers in a Digital Cinema Package (DCP) are metadata cues used for synchronization, automation, and playback control. These markers help digital cinema servers determine where specific elements of the composition begin and end.

Common Markers in DCP:

First Frame of Composition (FFOC) – The first visible frame of the composition when playback begins.

Last Frame of Composition (LFOC) – The last visible frame of the composition before it ends.

First Frame of Track File (FFTC) – The first frame of an individual track file (video, audio, or subtitles).

Last Frame of Track File (LFTC) – The last frame of an individual track file.

First Frame of Image (FFOI) – The first actual image frame, excluding black frames, countdowns, or leader elements.

Last Frame of Image (LFOI) – The last visible image frame before the video ends.

Picture Start – The point where the image track actually begins.

Sound Start – The point where the audio track begins, in case it has a delay or offset.

Marker Events – Custom markers used for automation, such as cueing subtitles, switching aspect ratios, or triggering external devices like house lights or masking.

These markers are primarily referenced in the CPL (Composition Playlist) and help ensure accurate synchronization and playback across different projection systems.

Delve deep into DCP

D-Cinema vs E-Cinema

D-Cinema is high-quality, standardized, and secure for theaters, while E-Cinema is more flexible, cost-effective, and widely used for non-theatrical digital screenings.

D-Cinema vs. E-Cinema: The Key Differences

Feature | D-Cinema (Digital Cinema) | E-Cinema (Electronic Cinema) |

Definition | The industry-standard digital format for theatrical releases. | A broad term for non-standard digital screenings (TVs, projectors, lower-quality digital systems). |

Resolution | 2K (2048x1080) or 4K (4096x2160). | Varies—could be 720p, 1080p, or other resolutions. |

Compression | Uses JPEG 2000 (high-quality, low-loss compression). | Uses standard video codecs like H.264, MPEG-2, or ProRes (higher compression, lower quality). |

Color Space | XYZ color space (designed for cinema projection). | Rec. 709, sRGB, or Rec. 2020 (TV and general video standards). |

Frame Rate | 24 fps (industry standard for theatrical projection). | Can be 25, 30, 50, or 60 fps (depends on the display device). |

Encryption & Security | Can include KDM (Key Delivery Message) for content protection. | Typically not encrypted, easier to copy and distribute. |

Sound Format | 5.1 or 7.1 uncompressed PCM audio (high-fidelity sound). | Often uses compressed AAC, MP3, or Dolby Digital. |

Playback Equipment | Requires specialized DCI-compliant servers and high-end digital projectors. | Can play on TVs, laptops, consumer projectors, and streaming platforms. |

Usage | Commercial movie theaters, film festivals, high-end screenings. | Corporate presentations, indie film screenings, airline entertainment, streaming, digital signage. |

Which One Do You Need?

If you’re distributing a film for theatrical release: You need D-Cinema (DCP format, JPEG 2000, XYZ color space).

If it’s for streaming, home video, or casual screenings: E-Cinema is fine (MP4, H.264, or ProRes, Rec. 709 color space).

Does DCP contain a DCDM file or JPEG 2000?

DCP (Digital Cinema Package) contains video in JPEG 2000 format, not DCDM. However, a DCDM (Digital Cinema Distribution Master) is often created before making a DCP.

DCDM is the intermediate master format - It is a high-quality, uncompressed format that ensures the best possible source for conversion into a DCP.

DCDM vs. DCP

Feature | DCDM (Digital Cinema Distribution Master) | DCP (Digital Cinema Package) |

Purpose | Archival master before making a DCP | Final, compressed package for cinema |

Compression | Uncompressed | JPEG 2000 (Lossy or Lossless) |

Color Space | DCI-P3 | XYZ (converted from DCDM during DCP encoding) |

File Format | Image sequence (TIFF or DPX) | MXF-wrapped JPEG 2000 |

Bit Depth | 12-bit | 12-bit |

Audio | Uncompressed WAV (Linear PCM) | WAV inside MXF container |

Subtitles | Not included in DCDM | XML subtitles in DCP |

DCDM File Components

A complete DCDM contains:

Uncompressed Image Sequence (16-bit or 12-bit TIFF or DPX files)

Uncompressed PCM Audio (24-bit, 48kHz/96kHz WAV)

Metadata (Color info, frame rate, etc.)

Why is DCDM Used?

It ensures that the highest quality version of the film is preserved before applying JPEG 2000 compression for DCP.

It is an archival format that can be stored for future re-encoding.

So, When Submitting for DCP, Do You Submit DCDM?

Not necessarily.

Most DCP services accept TIFF sequences or ProRes 4444, which they convert into a DCP.

If you already have a DCDM, it can be directly converted to a DCP with minimal loss.

DCI Standards

Resolution: 2K (2048×1080) or 4K (4096×2160) projection.

Brightness: Requires precise brightness calibration at 14 foot-lamberts (ft-L) for 2D projection and 3.5 ft-L for 3D projection.

Contrast Ratio: Minimum 2000:1 contrast ratio.

Color Gamut: Must meet DCI-P3 color space requirements.

Compression: Uses JPEG 2000 (J2K) for high-quality image compression.

Maximum Data Rate: 250 Mbps (megabits per second).

Interop DCP

An Interop DCP (Interoperable Digital Cinema Package) is an older, non-standardized format for DCPs that predates SMPTE DCPs. It was an interim solution before SMPTE DCPs became the official standard.

Key Features of Interop DCPs:

✅ Non-SMPTE Compliant – Uses an older MXF and XML structure.

✅ JPEG 2000 Video – Just like SMPTE DCPs, but with fewer color space options.

✅ 24-bit Linear PCM Audio – Stored in an MXF container.

✅ Timed Text Subtitles in PNG+XML – Unlike SMPTE, which supports SMPTE-TT subtitles.

✅ No Encryption Support – Interop DCPs cannot be encrypted with Key Delivery Messages (KDMs).

✅ Limited Frame Rates – Typically supports only 24fps.

Interop DCP vs. SMPTE DCP

Feature | Interop DCP | SMPTE DCP (Modern Standard) |

Standardization | Non-SMPTE compliant | Fully SMPTE compliant |

Encryption (KDMs) | ❌ Not supported | ✅ Supported |

Subtitles | PNG + XML (Image-based) | SMPTE Timed Text (TTML) |

Frame Rates | Only 24fps | 24, 25, 30, 48, 60 fps |

Color Space | XYZ (Limited support) | XYZ with better metadata |

Interoperability | Works in older systems | Required for modern cinema |

Why Does Interop DCP Still Exist?

Despite being outdated, Interop DCPs are still used because:

Many older projectors (pre-2012) only support Interop DCPs.

Some distributors and festivals still request it for maximum compatibility.

Not all cinemas have upgraded to full SMPTE compliance.

Note to remember

DCP XML is the required format for subtitles in a DCP.

Always send a multichannel audio track. Even if the mix is stereo, deliver a multichannel file with all other channels empty except for L and R.

If VFX is involved, send graded RAW files for VFX—preferably DPX or Cineon. (In some cases, an ungraded file may be required, depending on the type of VFX work.) The files must be uncompressed. If the footage was shot in RAW ( image sequence rather than a video file), the image sequence must be sent to the VFX department.

From the VFX department, you will receive a DPX file, which will be a series of uncompressed images, not a video. The VFX team may provide a reference video for placement in your edit timeline to check the quality of their work, but this reference video will not be used for grading.

Comments